Greek film-maker Athina Rachel Tsangari’s movie universe is

similar to the kind weaved by fellow, contemporary Greek directors like Yorgos

Lanthimos, Alexander Avaranos, etc. Their satires are populated with insecure

characters, caught in a lamentable state. Their film form observes details of

the characters’ body and interactions from a distance. Although the frames are

filled with white & grey shades and the atmosphere looks so calm, there’s a

feeling that violence or suppressed anxiety could explode at any moment. Compared to Lanthimos’

movies, Tsangari’s feature-film debut (“Attenberg”) and short-film (“The

Capsule”) is more light-hearted with a distinct brand of genuine fury,

surging now and then. From the all-female cast in 35 minute short “The

Capsule”, director Tsangari goes for an all-male cast for her second

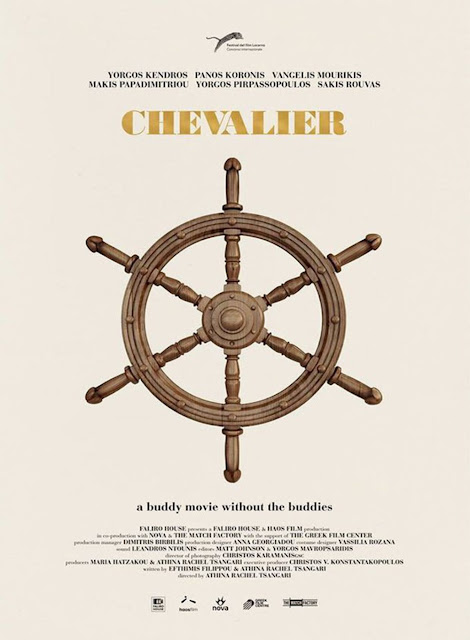

feature-film Chevalier (2015). Screenwriter Efthymis Filippou (“Dogtooth”,

“The Lobster”) has co-written the script with Tsangari which works as a

slow-burn comic drama with no big dramatic arcs. “Chevalier” is the study of

male ego or masculinity, expressing the (absurd) ways men compares and competes

with other social beings.

The film opens on a beautiful cove off the Aegean Sea. Men in

wet, rubber gear lurch around the shores. They observed from a distance from a

luxury yacht and pinned against the large cove, they look like ants. The

narrative is all about getting closer to take a biting look at their vanity.

Six healthy Greek men are on a fishing trip. The relationship between the

all-male passengers isn’t clear at first. Apart from these six people, three

males work in the kitchen below. They converse strictly in the socially

acceptable ways. The men have set out on their return trip to Athens. It seems

they are well-off to have escaped from the misery of Greece’s debt crisis.

Gradually, it becomes clear that the yacht is owned by elderly doctor (Yorgos

Kendros). His assistant Christos (Sakis Rouvas) has accompanied him. The other,

key four members of the ensemble are: doctor’s son-in-law Yannis his man-child

younger brother Dimitris and two of doctor’s friends – Yorgos & Josef. To

fend off the isolation they devise little games during dinner time. In one

game, they identify one another in terms of symbols or objects. A question like

‘If he was a fruit, what fruit he would be?’ will be asked and others should

guess the person.

|

| Men helping each other to get out of wet, rubber suit. The one who stands apart in the group is fully-clothed, socially awkward Dimitris |

This absurdist game causes tension between the six men. So

Christos suggests a new game called ‘Chevalier’. The goal is to decide on the ‘the

best in general’ by the end of the trip. Series of challenges will be suggested

and points will be assigned. The winner will get a Chevalier ring after the

return to Athens. They have to prove that they are the best in everything they

do. Some of the challenges are simple like ‘who is the fastest to assemble an

IKEA bookcase’, while many are comically absurd: to rate for the way they sleep

and eat, to rate their morning erections, to check blood sugar and cholesterol

levels, and to rate even for polishing silvers & washing the windows. From

doing domestic labor to showcasing their idiosyncratic macho behavior, these

mens’ sense of pride is often teased. The men’s relationship dynamics are

revealed and the buried feelings they have for each other swell up. This

seemingly simple competition tests their confidence as they all work as both

competitors and judges.

The yacht’s deck resembles the spacious, light-colored

contemporary housing of the moneyed elite. While at first it all seems luxurious

for a few days of fishing trip, the commencement of ‘the game’ and the ensuing

scrutiny brings the familiar claustrophobic feeling of being trapped in a small

place. Tsangari cleverly uses the reflective surfaces and mirrors in the room

to suggest the intense examination these men make on themselves and others.

There’s a hint of socioeconomic allegory in the way the characters in the

lowest deck (the cooks) discuss and bet on their master’s chance for winning

the game. The chaotic game of elites spreading among the members of lowest deck

is another smart critique (they also get infected by the diseased game plaguing

their master). However, director/writer Tsangari’s primary intention is not to

dwell on Greek upper class or their country’s financial problems. Lanthimos’

miserable characters in “Dogtooth” perfectly worked as the representation of

Greece’s apathetic rulers (of past and present). “Chevalier” is more a critique

on male gender, zeroing-in on their infantile behavior, ever-shifting brotherhood

and uncontrollable resentment. The commendable aspect of the film is that

Tsangari doesn’t use the bizarre premise of social games to include contrived

narrative arcs. The sequences when old wounds surface and new wounds are cut

open are designed in an organic manner.

|

| One of the movie's dryly funny moment when Dimitris sings a song and his brother goofily dances with a flare |

The director and her DP Christos Karamanis uses the limited

space creatively to minutely observe the anxieties of men in closed quarters.

Athina Tsangari says she initially thought of putting these men in a luxurious

house, but that set-up would have only resembled the traits of numerous

single-atmosphere thrillers. The wide-screen beauty of the sea, islands and the

cruise works a better battleground for this critique. The natural fear that

accompanies them in such trips is a gain to the darkly comical tone. Some of

the clever part of the proceeding includes the abrupt cutting, which at times

confuses on who won a particular game. With such a well-crafted look and

positive aspects, “Chevalier” could have been a great satire if only it has

achieved an emotional resonance. The director’s observations are clean and

precise, but as the narrative progresses, the chief interest is on making a

statement. The characters’ behavior in the middle and later parts are only used

to serve the gender statement. She conveys an incredible metaphor through the

game about how men take every simple thing in life as some kind of tournament. I

liked how this film has pondered over the insecurities of men (physical &

mental). In majority of cinema, women’s insecurities are depicted and that too,

predominantly from an apathetic or derisive perspective. Tsangari de-dramatized

gaze is not that of a woman director looking at men like guinea pigs in the

lab. She isn’t dehumanizing the characters or trivializes their inner pain. But,

at the same time the characters aren’t profound and I couldn’t get an emotional

hold on them. Efthymis Papadimitriou as Dimitris is the only effective

character, but even that is a testament to the actor’s performance than the

characterization. It is good that the director side-steps from dramatization,

but it don’t fend off the monotony that sets in. As a director, she is more nuanced in staging

the scenes. For example, you see the doctor and Christos rowing in the exercise

machine in perfect sync. It observes their bond. In the later half, in the same

rowing exercise machine, the doctor and Christos are entirely out of sync,

suggesting little cracks in their relationship.

Chevalier (105 minutes) is a darkly funny and slightly displeasing

exploration of the inherent stupidity associated with the perception of masculinity.

About Author -

Arun Kumar is an ardent cinephile, who finds solace by exploring and learning from the unique works of the cinematic art. He believes in the shared-dream experience of cinema and tries to share those thoughts in the best possible way. He blogs at Passion for Movies and 'Creofire'.

Readers, please feel free to share your views/opinions in the comment box below. As always your feedback is highly appreciated!

Chevalier (2015) Trailer (YouTube)

People who liked this also liked...

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for sharing for valuable opinion. We would be delighted to have you back.