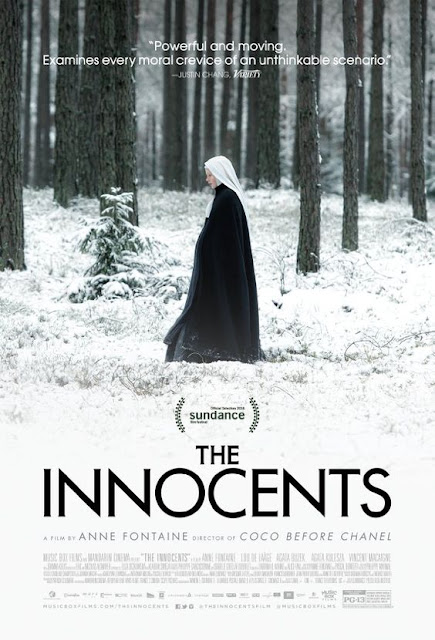

French film-maker Anne Fontaine’s The Innocents (aka

‘Agnus Dei’, 2016) shines light on one of the agonizing chapters of World War II. After

the winter offensive of 1945, during the so-called liberation of Poland, waves

of women and girls were raped in Polish cities, which fell under the control of

Red Army marauders. Soviet soldiers were also engaged in widespread theft of

personal property. Until the disintegration of Soviet Union, the subject of

sexual violence against Polish women was blacked out from Poland’s

historiography. Fontaine’s movie opens on the winter of 1945, at a Polish convent.

At the crack of down, a group of Benedictine nuns sing a serene hymn to the

lord. The camera gradually zooms out before resting on the face of a young nun.

The sense of anticipation exhibited by the nun seems to suggest an affliction,

lying beneath this tranquility. The young nun walks out of the convent in the

snow-drenched landscape in search of a doctor. An orphan boy leads her to the campus of French Red Cross workers,

who are reluctant to breach the code and make a trip to the nunnery. Mathilde (Lou de Laage), a doctor’s assistant for the Red Cross, gazes outside her window and looks

at the anxious nun, kneeling down in the white snow and praying. The frame

lingers closely on Mathilde’s beautiful face, wisps of cigarette smoke flowing

around her. The muted emotions give us the feeling the she is going to

transgress the rules to go with the nun, which will change her

life forever.

Film Theoretician Bela Belazs often talks about the power of

expression through the well-crafted close-up shots of human face. He says that

human face marks the ‘very instant in which the general is transformed into

particular’. Similarly, in The Innocents, Fontaine tries to evoke the

character’s inner torment by observing the fleeting emotions in their faces.

When Mathilde first enters into convent she perceives it as a peaceful refuge in

the times of war. She is taken to a pregnant woman whom the authoritative

abbess (Agata Kulesza) says is thrown out by her parents. Asking a young sister

Maria (Agata Buzek) to hold the single glowing lamp, Mathilde performs a caesarean

on the woman. It is only on her second visit, Mathilde learns about the painful

cross the sisters carry within them. The sisters were raped by Soviet

‘liberators’ during a three-day raid. Seven of the nuns are in the late stages

of their pregnancies. Various conflicts seem to confound the nuns: some fear

eternal damnation; some are ashamed to let the doctor to do physical

examination; some feel that their faith is also violated alongside their flesh.

|

| Lou De Laage plays the central character Mathilde. She gives a more composed performance, which is the exact opposite of the role she played in Melanie Laurent's "Breathe" |

Mathilde is an atheist, raised by communist parents. She is

a sexually liberated woman who struggles for respect in a profession dominated

by scoffing males. This may be the initial reason to breach the code and help

the Polish nuns. She wears khaki shirt & pant and a blue scarf, which seem

to reflect the sadness pervading the war-torn land. During one of her trip from

the convent, Mathilde is stopped by Russian soldiers. She is assaulted and

nearly raped (a Russian commander stops the soldiers). This traumatic experience

brings her closer to the nuns’ inner torment. When she wakes up next day to the

soothing prayer chant, Mathilde finds the quietude that’s missing in her life.

Mathilde later earns the sisters’ respect and love when she blockades a big

disaster.

Anne Fontaine and DoP Caroline Champetier somber, painterly

images brilliantly express the truth and beauty amidst the bleakness. The muted

palette of blue, black and grey subtly captures the featureless frozen

landscape and the frigid faces. The collective depression inside the convent is

efficiently suggested without any psychological explanations. Director Fontaine

focuses on emotionally resonant smaller details. For most part of the

narrative, she shows amazing restraint. In one scene, Mathilde touches the

pregnant belly of a young nun. The nun immediately explodes in laughter, for it

may be the first time as a adult she is touched by another adult in a

non-violent manner. But, as sister Maria looks at the young nun, the sudden

laughter is replaced back with muteness. It’s a very small moment in the

narrative which conveys the nuns’ repressed lives. The initial C-section scene

is filmed in a disquieting manner, which seem to suggest the brutal violations

faced by women of the land. Even in the dialogue-heavy scenes, Fontaine lingers

on the pauses and silences to create a haunting effect. Sister Maria’s calm explanation

of faith (“Faith is 24 hours of doubt and one minute of hope”) stays long after

the end-credits. Nevertheless something

seems to be missing in the film which stops it from being a masterpiece or a

must-see work. The flaw I felt was in the script written by Alice Vial, Pascal

Bonitzer, Sabrina B. Karine, and Fontaine.

|

| One of the movie's emotionally resonating and beautifully framed moment. Happens after Mathilde smartly saves the nuns from impending disaster |

The narrative tries to be about a French woman caught in

extraordinary circumstances; about nuns and the possible annihilation of their

bodies & faith; and an allegory of a nation looking at aftermath of a

brutal invasion. The narrative moves in between the themes, sometimes robbing

us of the space to care for individual characters. The scattered examination of

spiritual crisis, horrors of war stops it from being a sharply focused

character study on three women – Abbess, Sister Maria, and Mathilde. The

terrific actress Kulesza is burdened with a very two-dimensional character. Apart

from the confrontation with Russian soldiers, Mathilde has little to offer to

the central crisis or drama. The character of Samuel – Mathilde’s superior and

love interest – was under-developed as he is only meant to tell Mathilde that

not all Poles in WWII were good ones. Even his contradictory action of helping

the nuns isn’t connected well with the main themes. “The Innocents”, thanks to

impeccable cast (Lou De Laage was charismatic) and visuals, is still a poignant

and painful portrait of womanhood, in times of war. But with robust script, it

could have been a wonderful allegory on women condition (the women in The

Innocents don’t feel safe, whatever their ideology and costume choices are). The

screenwriters also haven’t compellingly put forth the question of an individual

restoring the belief in God after being tormented (physically & mentally) in

such a vile manner. The ending definitely feels good, although we feel that the

initially promised profound exploration of afflicted human souls is only

tentatively realized.

The Innocents (116 minutes) breathes in a glimmer of hope

into a period of bleakness. It is consistently absorbing and maintains the

artistic integrity in telling a little known wartime atrocity. With a shrewd

focus and profundity, it could have been a masterful film about female

persecution and spiritual crisis.

Anne Fontaine Interview -- Rogerebert.com

Readers, please feel free to share your views/opinions in the comment box below. As always your feedback is highly appreciated!

Innocents (2016) Trailer (YouTube)

Previous Post: Netflix becomes the global home to SRK

Next Post: La La Land: Movie Review

Complete List of Reviews

Readers, please feel free to share your views/opinions in the comment box below. As always your feedback is highly appreciated!

Innocents (2016) Trailer (YouTube)

Previous Post: Netflix becomes the global home to SRK

Next Post: La La Land: Movie Review

Complete List of Reviews

People who liked this also liked...

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for sharing for valuable opinion. We would be delighted to have you back.